MANILA, Philippines—A “fragmented” region is in the interest of China as it could throw its weight around more easily when it is engaged only in bilateral talks instead of a unified Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean).

This was pointed out by Don McLain Gill, a geopolitical analyst, who said that the idea of engaging bilaterally, especially on issues of security, “has been a go-to option by China for the longest time.”

He told INQUIRER.net that China “understands its technologies and vast material capabilities, and it often sees them as an advantage over its less powerful neighbors,” which include the Philippines.

“China thrives in fragmentation,” Gill said while stating that this is why China has always targeted a widening of cracks in Asean.

RELATED STORY: China protests Philippines’ claim of extended continental shelf

As Gill stressed, this is because China could really throw its weight around in bilateral negotiations, or consultations that involve only two parties, like China and the Philippines or China and Malaysia.

For instance, Beijing’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has sent a communication to the Malaysian Embassy in China this year to assail actions by Kuala Lumpur that “infringe” on what it claimed was Chinese sovereignty over areas covered by its nine, now 10-dash line.

READ: China’s WPS lies: From baseless dashed line to ‘indisputable sovereignty’

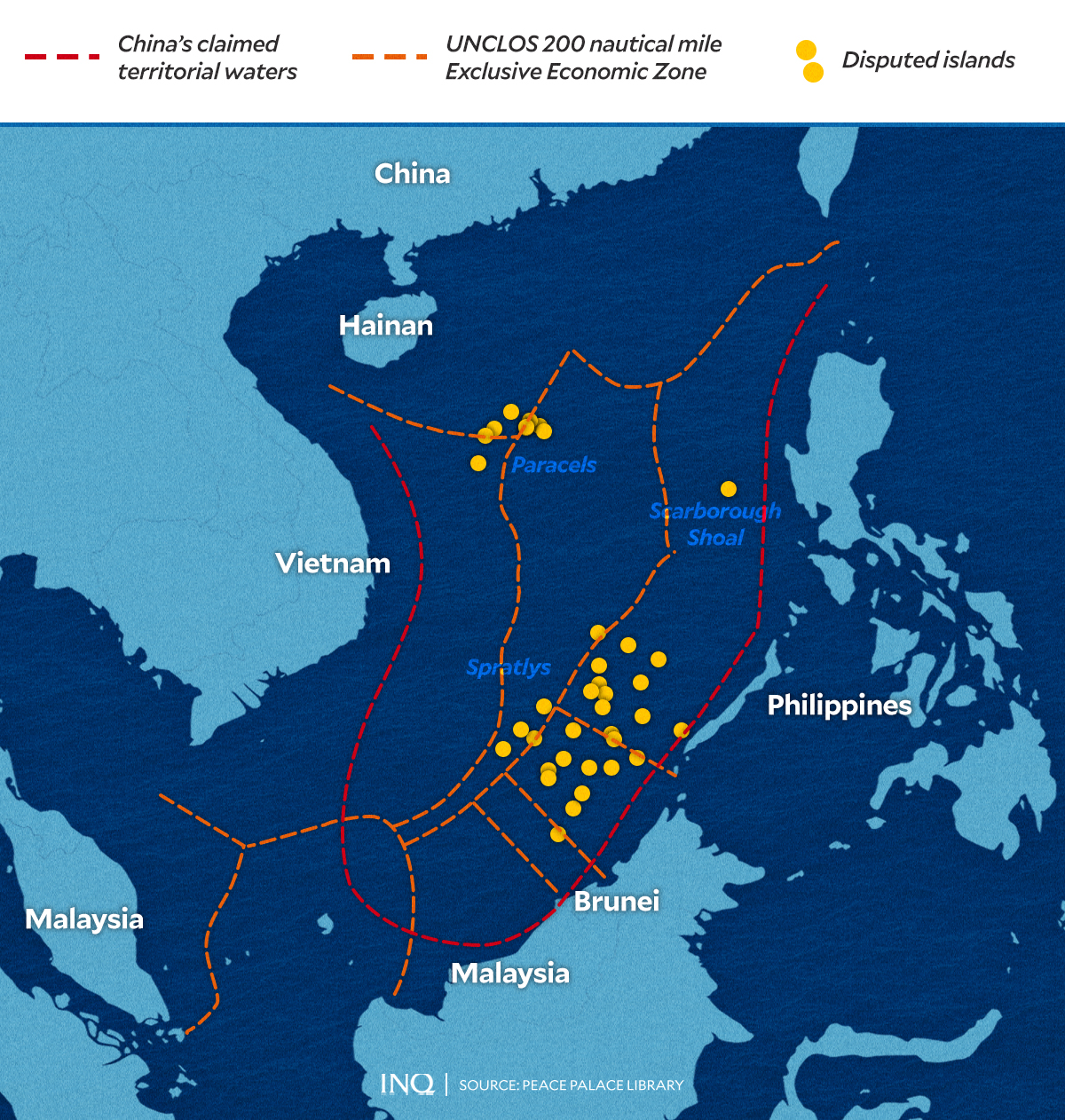

China’s dashed line has already been declared baseless by an arbitral tribunal formed to decide on a case the Philippines filed against China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2013.

PH a ‘victim’

This strategy of China was highly visible when Rodrigo Duterte was president, Gill said as he pointed out the “level of pressure that China was able to impose on the Philippines when Manila was pursuing a more appeasement-driven approach towards Beijing.”

Back in 2017, the Asean did not mention the 2016 arbitral decision that invalidated China’s claims over most of the South China Sea in its 25-page joint statement even when the Philippines was Asean chair that year.

READ: China’s West Philippine Sea gray zone tactics: It’s still war

For Gill, a lecturer of international studies at the De La Salle University, this was in itself an “impediment” for the Philippines to really maximize its ability to assert its sovereignty and sovereign rights over the West Philippine Sea.

Joshua Espeña, a defense analyst, told INQUIRER.net that Duterte “fell into the notion of China’s peaceful rise and then tried to justify his foreign policy stance when his premise went spirally wrong.”

READ: China’s bid to break Asean unity bound to fail – Teodoro

He explained that Duterte failed to realize that China would not act in the interest of the Philippines as any great powers would. “From a historical standpoint, I’d say his presidency indicates the birth pains of the country’s evolving strategic culture,” Espeña said.

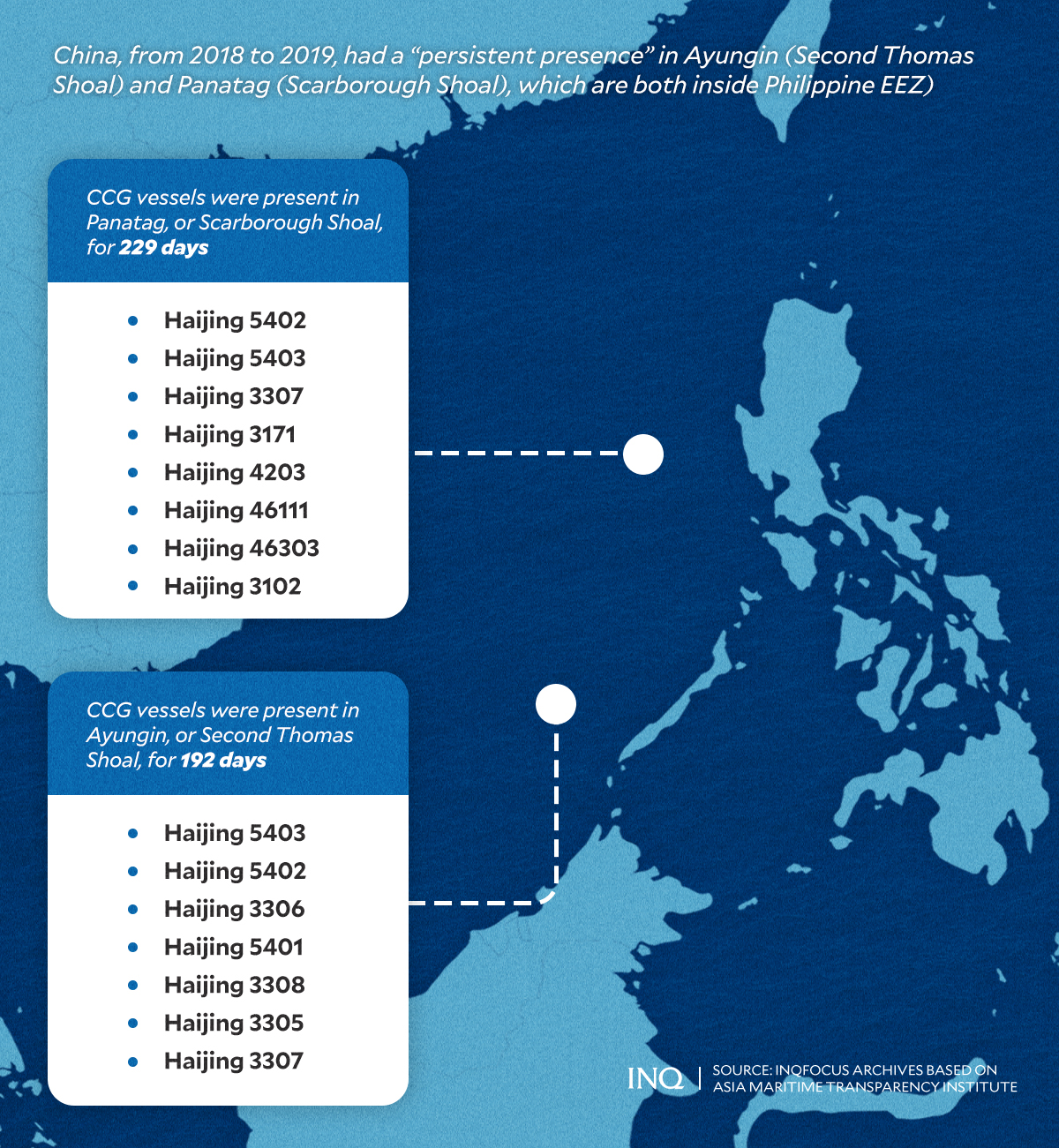

Even when Duterte sided with Beijing in many instances, China Coast Guard (CCG) vessels still maintained their presence in the West Philippine Sea from 2018 to 2019, based on data from the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI).

READ: West Philippine Sea monitor spots China ‘monster ship’ near Ayungin

In his most glaring declaration of siding with China, Duterte echoed Beijing’s position on the arbitral ruling calling it just a piece of paper he can throw in the waste basket.

Silent intimidation

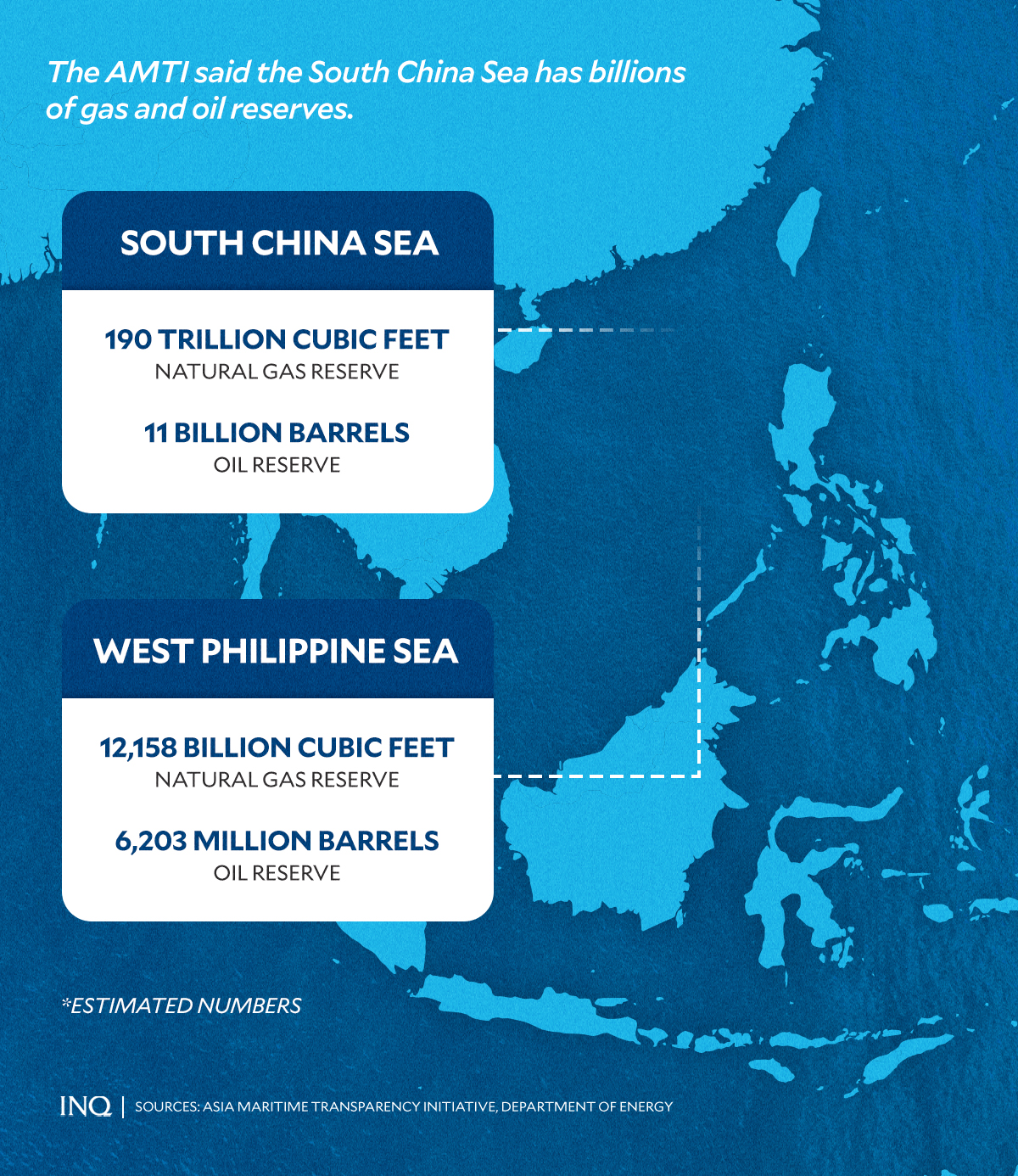

Back in 2022, based on a report by Radio Free Asia (RFA), lawyer Jay Batongbacal, pointed out a possible coercion from China as the reason for the decision of the Philippines to suspend oil and gas exploration within its own exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

Batongbacal, director of the University of the Philippines’ Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea, said that China has been pressuring Manila to either accept its proposal or stop drilling.

RELATED STORY: China’s nine-dash line: A dangerous fiction even in the movies

“Through diplomacy and the actions of the CCG, Beijing has been trying to coerce Manila to stop conducting seabed exploration and research activities in the West Philippine Sea until the latter submits to China’s conditions for joint development,” Batongbacal said in the RFA interview.

It was in 2018 when the Philippines and China signed a Memorandum of Understanding for joint oil and gas development in the West Philippine Sea inside Philippine EEZ.

RELATED STORY: Malaysia gets taste of China West Philippine Sea bullying

But a few years later, the Department of Energy said that the Security, Justice, and Peace Cabinet Cluster suspended oil and gas activities because of China’s harassment of survey vessels by service contractors.

Negotiations with China were likewise cited as a reason for the suspension.

‘Divide and conquer’

Back in 2012, even after intense discussions, the Asean did not issue a joint statement for the first time in 45 years as foreign ministers failed to reach an agreement on how to deal with China’s aggression in South China Sea.

Then in 2016, a joint statement by Asean that mentioned the aggression in the South China Sea had been retracted for what has been said to be a “need for amendment.”

The statement “expressed serious concerns over recent and ongoing developments, which have eroded trust and confidence, increased tensions and which may have the potential to undermine peace, security and stability.”

As Gill said, “immediately, [one] can see the Chinese influence there,” pointing to reports that the draft of the 2012 joint statement has been shared with Chinese interlocutors, while in 2016, it is believed that the statement drew protest from China.

He stressed that this eventually served as a signal for Beijing to use a model that would ensure that institutions, like Asean, will remain fractured, especially with regard to passing on proposals and suggestions, and statements on maritime security.

Espeña, meanwhile, pointed out that China’s tactic is “audacious and comprehensive given how Beijing understands that controlling the first island chain requires a piecemeal win in the fashion of diplomacy.”

“Because a multilateral approach would mean a multilateral counter-response to balance the risk of dealing with China,” he said.

‘We’ only

For Gill, this in itself indicates that China “prefers bilateral modes of consultation, particularly in trying to address security issues because one, China does not really intend to resolve these issues in favor of its smaller neighbors.”

“Rather, [it] seeks to throw its weight around to maximize its strategic gains from that particular situation,” he said, pointing out that “we’ve seen this in China’s relations with Bhutan and even with Nepal.” said Gill.

As China has been increasing its claims in these areas, it exerts pressure on keeping it bilateral, so it pushed aside the idea of involving India, for instance, Gill said.

Likewise, “throughout the greater continent of Asia, China has pushed for a global security initiative, which centers on the idea of Asia for Asians, but also ensuring that dialogue mechanisms are bilateral.”

“So this, again, is a way to impose a regional or continentally exclusionary policy that would ensure that China has the advantage in negotiations without the inclusion of extra regional powers, particularly in the West,” he said.

Last March, China stressed that in its issue with the Philippines regarding the South China Sea, there should be no foreign interference, infringement and provocation, saying that a proper management of differences is needed.

There is “no bigger factor than the US interference,” it said.

No sincerity at all

Under Duterte, Gill said that the government “thought that China acts on the basis of trust and confidence and that it wants to be a better neighbor,” stressing that this is where Manila “faltered.”

“That wasn’t the case. Bilateral negotiations can only go far if there is joint recognition between both parties of the need to develop sustainable and effective and friendly ties for the purpose of peace, based on international law,” he said.

Gill pointed out that “China does not believe in that. It believes in taking as much as it can by taking advantage of every situation possible, and that is not something that you would like to have as a bilateral counterpart, so that is what China is all after.”

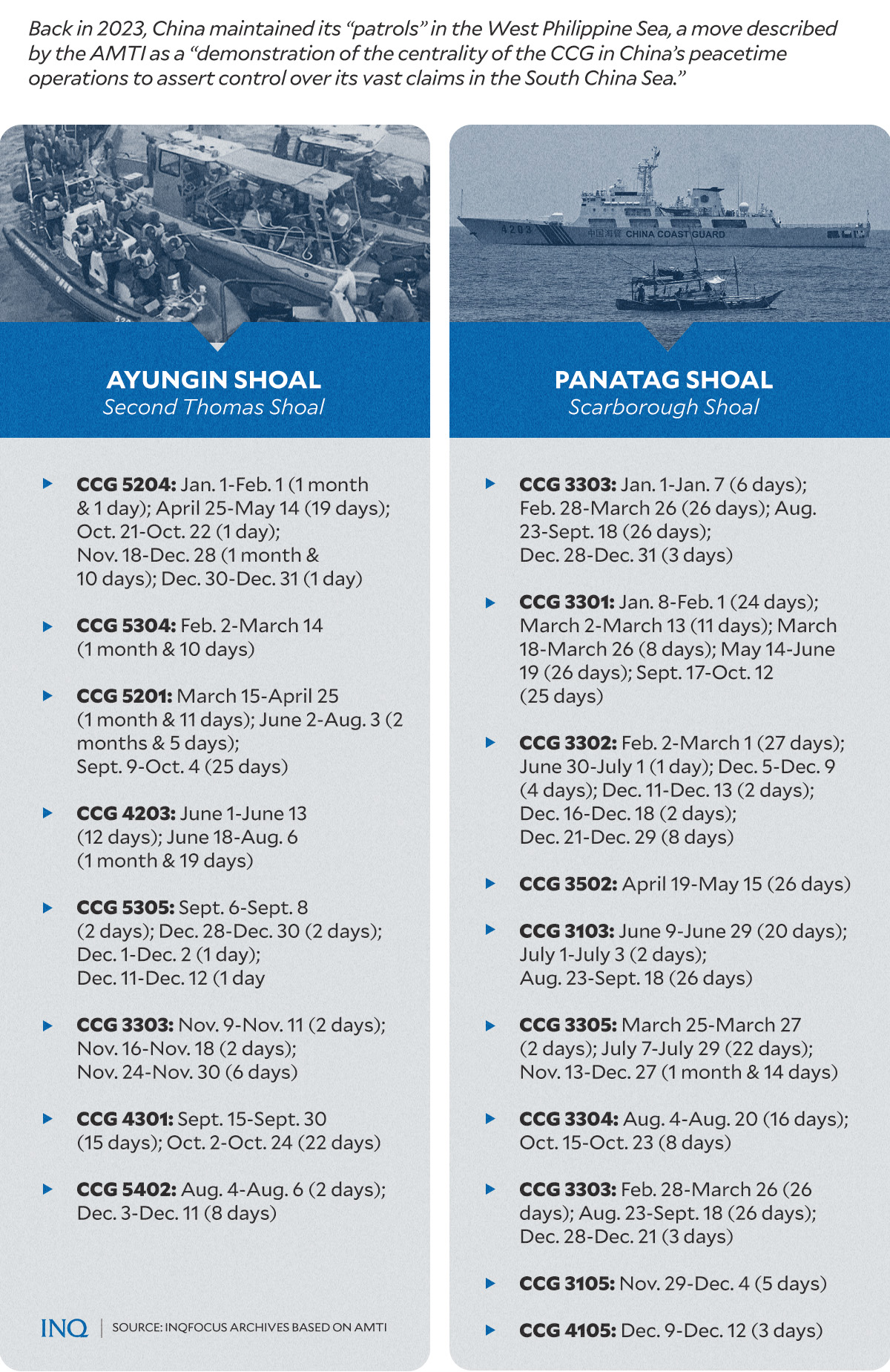

Based on data from AMTI, China has a “persistent presence” in the West Philippine Sea through its “patrols”, a move described as a “demonstration of the centrality of the China Coast Guard in China’s peacetime operations.”

Here are some instances cited by AMTI:

- Ayungin/Second Thomas Shoal

- CCG 5204: Jan. 1-Feb. 1; April 25-May 14; Oct. 21-Oct. 22; Nov. 18-Dec. 28; Dec. 30-Dec. 31

- CCG 5304: Feb. 2-March 14

- CCG 5201: March 15-April 25; June 2-Aug. 3; Sept. 9-Oct. 4

- CCG 4203: June 1-June 13; June 18-Aug. 6

- CCG 5305: Sept. 6-Sept. 8; Dec. 28-Dec. 30; Dec. 1-Dec. 2; Dec. 11-Dec. 12

- CCG 3303: Nov. 9-Nov. 11; Nov. 16-Nov. 18; Nov. 24-Nov. 30

- CCG 4301: Sept. 15-Sept. 30; Oct. 2-Oct. 24

- CCG 5402: Aug. 4-Aug. 6; Dec. 3-Dec. 11

- Panatag/Scarborough Shoal

- CCG 3303: Jan. 1-Jan. 7; Feb. 28-March 26; Aug. 23-Sept. 18; Dec. 28-Dec. 31

- CCG 3301: Jan. 8-Feb. 1; March 2-March 13; March 18-March 26; May 14-June 19; Sept. 17-Oct. 12

- CCG 3302: Feb. 2-March 1; June 30-July 1; Dec. 5-Dec. 9; Dec. 11-Dec. 13; Dec. 16-Dec. 18; Dec. 21-Dec. 29

- CCG 3502: April 19-May 15

- CCG 3103: June 9-June 29; July 1-July 3; Aug. 23-Sept. 18

- CCG 3305: March 25-March 27; July 7-July 29; Nov. 13-Dec. 27

- CCG 3304: Aug. 4-Aug. 20; Oct. 15-Oct. 23

- CCG 3303: Feb. 28-March 26; Aug. 23-Sept. 18; Dec. 28-Dec. 21

- CCG 3105: Nov. 29-Dec. 4

- CCG 4105: Dec. 9-Dec. 12

As Gill said, this is something that the Philippines is realizing now – “that China likes to throw its weight around.”

“This is why we are trying to include our partners into the discussion, into the picture, as well, to ensure that the maritime domain remains free and open,” he said, pointing that this is “in our interest as an archipelagic state,” Gill said.